What made you choose the topic “Action Art. Art that challenges” (“Action Art. Arta care provoacă”) for the CAMPart online mentorship program? In how far do you think the topic is relevant for the new generation of artists?

We’ve all asked ourselves these days what our role is within an art system that has shown itself dysfunctional under pandemic conditions and which can only remain viable if it undergoes a transformation on all levels (artist, work, audience, institution). What I have in mind is a transfer from the classical elements of the artwork-as-object to artistic practices that aim to solve issues pertaining to society, the economy, ecology, etc. This process started in the 20th century, when the ideologies of the historical avant-garde took down the artwork from the pedestal of that consecrated institution, the museum, in order to place it face to face with the issues of large-scale industrialization. Later, in the postwar period, actions like those of Joseph Beuys freed the artwork from the market of consumer capitalism, establishing it instead as a unique form of individual freedom given to each of us to free ourselves from the socio-political experiments we are undergoing. Creativity and critical thinking therefore became the instruments of a social sculpture that could gradually spread from individual to individual into society at large. Furthermore, in the current context of globalization, various international contemporary art platforms are doing their part in solving the critical state of the Earth. In festivals like Ars Electronica Linz / Global Shift (2019) and ZKM Karlsruhe / Critical Zones. Observatories for Earthly Politics (2020), artists and researchers have debated the state of confusion humanity is facing because of climate change and its causes. What is relevant here is the fragmentation of the Earth’s iconic image into power/control territories that eventually lead to the excessive extraction of resources through industrialization, deregulated exploitation of the workforce, impoverishing populations, migration, bio-warfare, manipulation through the media, etc… All these “critical zones” create conditions unfit for life.

Applying the concept of critical zones to the field of art leads to the creation of a “critical art zone,” in which one can problematize both the process of art making as well reality in general. So the course I proposed, Action Art. Art that challenges, offers young artists the possibility of examining the facets of these profound transformations, in which the artist overcomes their condition of aesthetic object creator, becoming instead an ecologist overlooking a macro-transformation of humanity and reality (Joseph Beuys, in Social Sculpture, 1970). At the same time, the artist becomes a design scientist (Gene Youngblood, Expanded Cinema, 1970), disseminating the versatile relationship between art, science, and technology. And in the context of telecommunication, the work gains a certain openness on the level of its codes of execution (Umberto Eco, Opera Aperta, 1962), which allows the viewer, as participant/user/consumer, to continuously enrich it, thereby becoming its co-author. In the context of the course, we went through ideologies, performative practices, and technological argumentation strategies developed by paradigmatic avant-garde artists, but also by artists in the last decades, which gave us a solid base for debate, which is necessary to get young artists adapted to aspects of critical thinking (observing/analyzing/evaluating), as well as to the possibility to using creativity as an instrument for generating new fields of coexistence (from individual creativity to the collective creativity of urban and global proximity).

Is there a connection between studio practice and teaching practice?

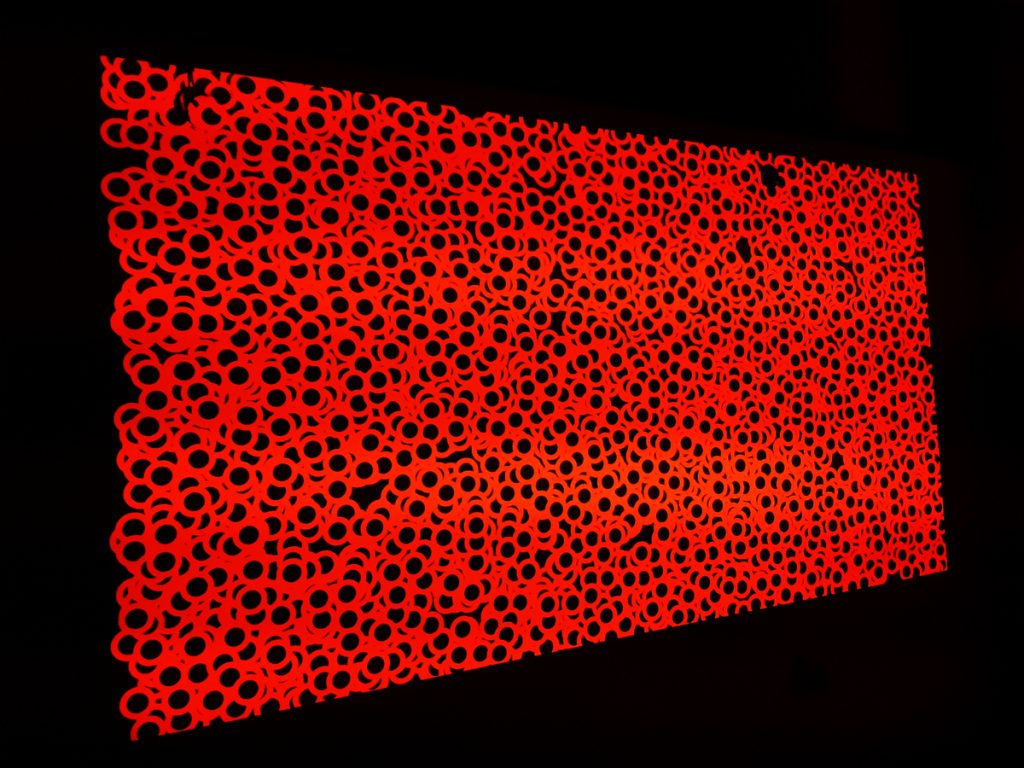

The digital installations that I create are conceived with the active participation of the audience in mind, giving people the possibility to contribute to the materialization of the work and, importantly, to its dissolution into a multimedia environment with synesthetic and synaesthetic effects. With the help of interactive-immersive intermedia sensorial strategies, I consistently tackle the ways in which technological augmentation creates an expanded perceptive experience (visual, auditory, tactile, kinesthetic), which also has a major impact on artistic processuality (the status of the telematically distributed, integrated media artwork), but also on the level of reality as such, due to the proximity of telecommunication technology (the status of homo integralis, immersed in a trans-locational reality). Therefore, in the context of the global media work, each of us can bring their own creative contribution, because this artwork is open in nature and its author eventually becomes a collective one dispersed throughout a network.

From this stems the collaborative nature of my intended practice. The involvement of creative personalities from the field of art and beyond is very important. But probably most important is the exchange of information between generations, as young artists bring in technological savvy and a freshness of ideas. That’s why, in 2020, I launched the Tehnoarte (online/offline) platform, as a complement to formal art education (for school/university students and young artists), with the idea of expanding traditional techniques with the help of performative practices based on technological augmentation. Among the platform’s educational projects, I would mention the Action Art (Draw/Paint/Sculpt/Code) workshops, which offer a multisensorial approach to drawing, painting, and sculpture, expanded through the use of sensors and digital programming. The platform is also addressed to young people in other fields, giving participants the possibility of activating their performative artistic skills and of becoming integrated into a creative community, through an interdisciplinary approach.

Were you inspired by your contact with the young artists? What would you say to artists who are just starting out and looking for a direction?

Encountering young artists is certainly special. I give them full credit for their highly comprehensive understanding of reality, even if they are not fully aware of it. They have the opportunity of being trained in inter- and transdisciplinary classes through their university mobility programs, and the fact that they can easily travel helps them clear their minds of the techniques of object-based art in favor of conveying volatile media content. I am often astounded by their ability to express, in an international language, the concepts that they study on the most important contemporary art platforms. Furthermore, the fact that they have an intuitive understanding of telecommunication technology helps them hyperpolarize an entire sphere of knowledge (the noosphere), characterized by a depth of information never before seen and by a limitless distribution, as anthropologist Teilhard de Chardin predicted at the beginning of the 20th century. We can therefore outline the profile of the “proximity artist,” who, like an agent charged with changing reality, causes the members of a network to in turn become creative, both individually and collectively, which effects positive change within society. That is why I would like to encourage young artists to become aware of the possibilities they have before them, and the fact that they are able to put in the creative energy to bring this path to fruition is a merit both to themselves and to the communities they are part of.

How do you see the reinvention of art practice, of art making and exhibiting systems, in the context of the current changes, which will impact the art world? What do you think will change in the long run?

One of the pioneers of the historical avant-garde, Wassily Kandinsky, used to dream that one day art would know that monumental dimension that would unite the force of all artistic disciplines within it (Concerning the Spiritual in Art, 1911). It is perhaps no coincidence that his vision reiterated that utopia conceived by writer Israel Zangwill (The Melting Pot, 1908),where all nations, ethnicities, cultures, etc. would merge together, in the spirit of the French Revolution. It seems that now, one century later, the pandemic has helped us reach this state of essential unity, even though it benefits from that “telematic embrace” that Roy Ascott talked about, which forces us, in an almost brutal way, to abandon the levers of an obsolete, fragmented world. I therefore believe that the future of art belongs wholly to creative communities capable of channeling creative energy at the level of society as a whole, and that is because these communities enjoy an eclectic and bubbling energy which the classical structure of the art academy lacks, unfortunately. It is certain that the telematic hyperpolarization of creative communities is capable of uniting thousands of years of fragmentation, during which disciplines, languages, and practices were separated according to various criteria and which are now returning yet again to a state of global integrative unity.

Interview with artist Aura Bălănescu